The night we let go Longyearbyen it was snowing hard and given that it was the third of October and we were just a few hundred miles from the North Pole the world was visually much as I had expected to find it. I could just barely make out the ruins of mines and shacks that had served the residents of Advent City, now a ghost town, one of many such abandoned settlements. This high arctic archipelago was so far north in fact that there has never been an indigenous peoples—archeologists have just found traces of summer hunting parties and the wreckage of some of the first European arctic whaling stations. It had rained hard the entire month of September—which was doubly bizarre because the high arctic is mostly so cold and dry year round that is classified as a polar desert and it was officially the beginning of winter. In just a few short weeks the sun would be so low on the horizon it would not scale the mountains to the east any longer ushering in the four months of polar darkness. I had looked forward to sailing into winter, into that long night and finally everything seemed to be coming together just has I had imagined it.

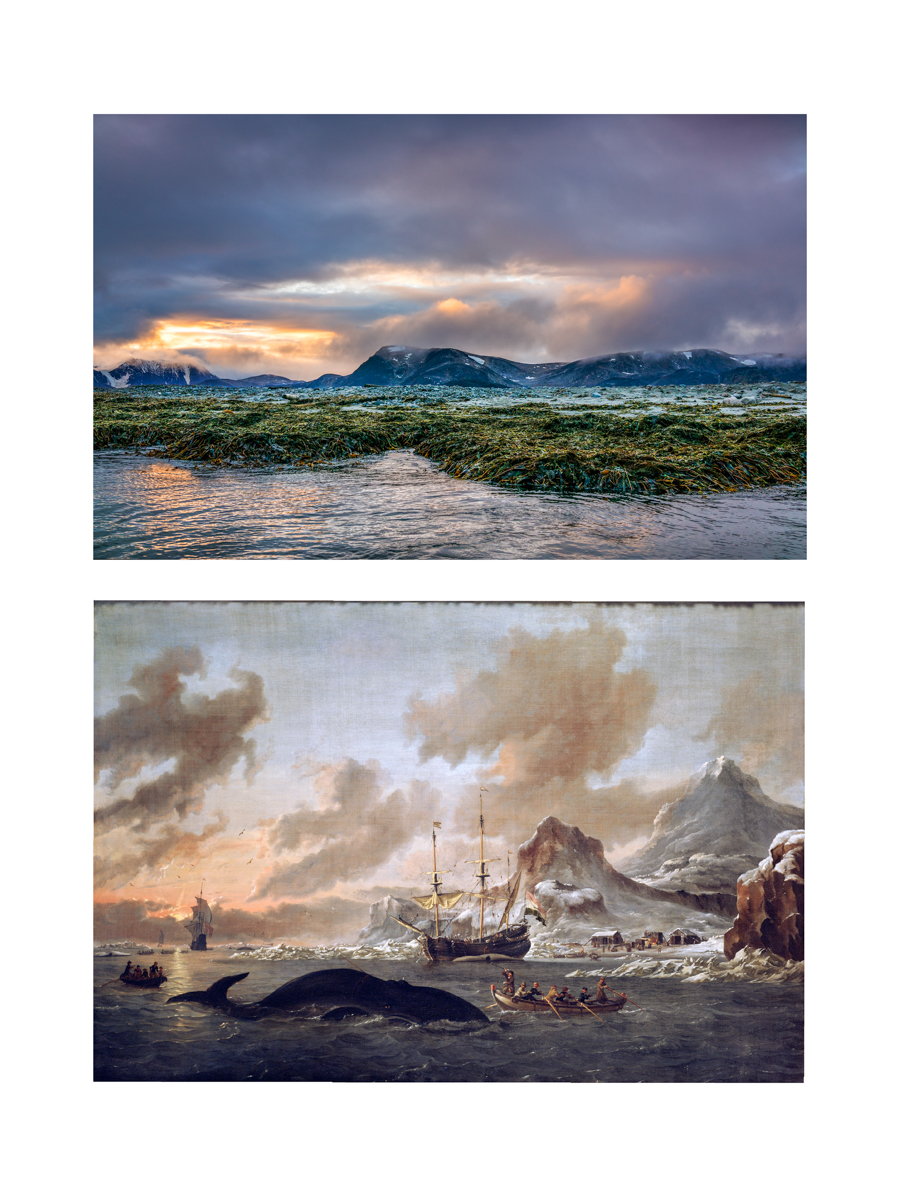

I had planned to photograph the ruins of summer whaling stations established on northwestern edge of the island of Svalbard—long known as Spitzbergen. The earliest stations had been established in the first two decades of the 1700s during the first European oil boom, during what will prove to be at the advent of the Industrial Revolution. I had a pretty good idea—I thought—of what I might find there. I had after all participated in archeological digs in arctic Alaska and I understood fairly well how the year-round cold and dryness helped to preserve any organic material left on the surface . What I didn’t know yet—what we will discover firsthand as we sailed those turbulent late autumn early winter seas was that 2016 was the worst year on record for summer polar ice melt and the degradation in the permanent ice had opened up such a vast expanse of open water the shimmering dark surface had warmed the arctic basin and now the north pole was having trouble cooling down for winter. The extreme and unusual warmth triggered heavy rains that kept stripping all the new snow from all the mountains all the way North triggering landslides and glacial surges. Just two days in we sought shelter for two and a half days along side a glacier during a particularly violent storm and when the rains ended this was the site that greeted us—winter mountains stripped bare and transformed into shimmering black mud slopes. The crew had dropped both anchors and let out 260 meters of chain to keep us from being dragged out into the sea and still even with the engine to boat was being pulled from safety, spinning and spinning until the chains were tangled. I knew then that something was up—that something was very strange. We were starting our journey almost 800 miles North of Barrow Alaska—or 1200 miles north of Oslo Norway and the weather was warm at wet.

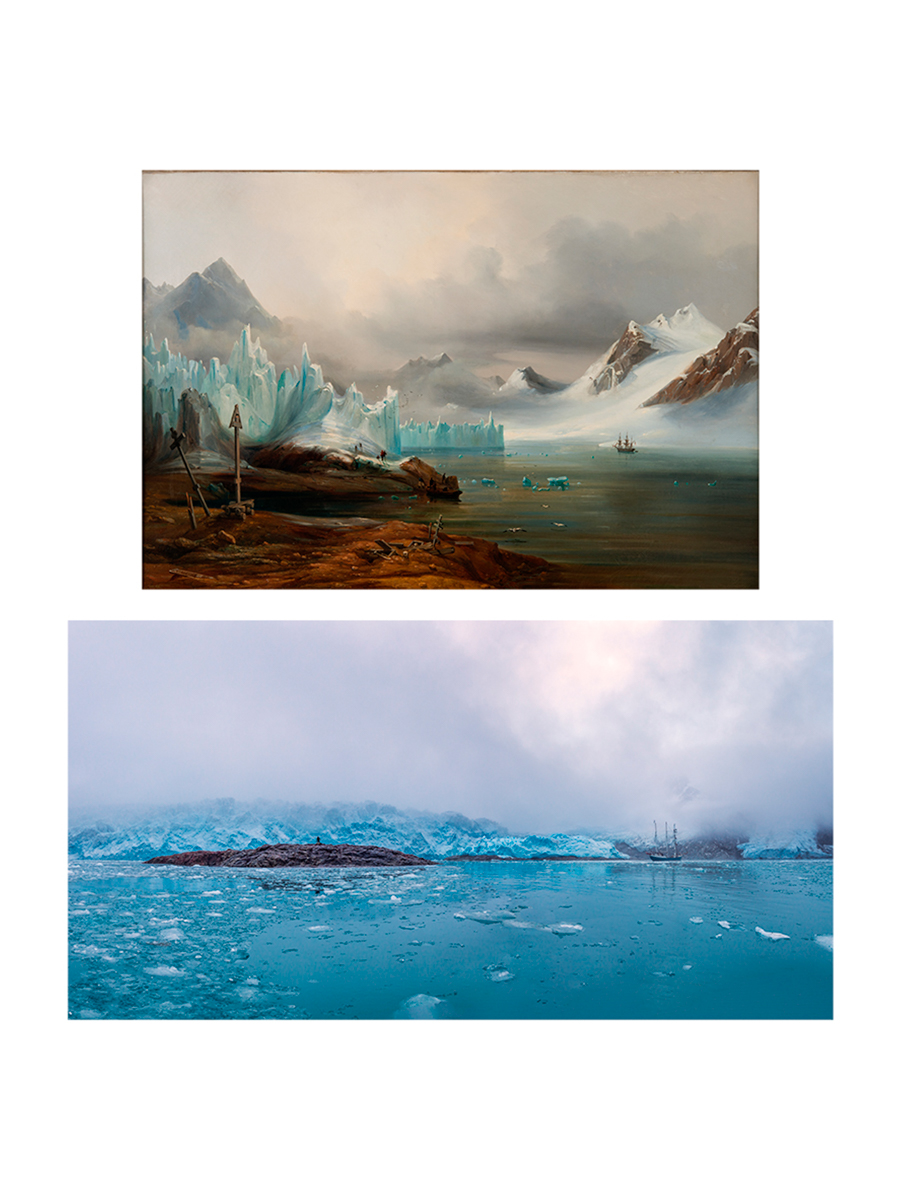

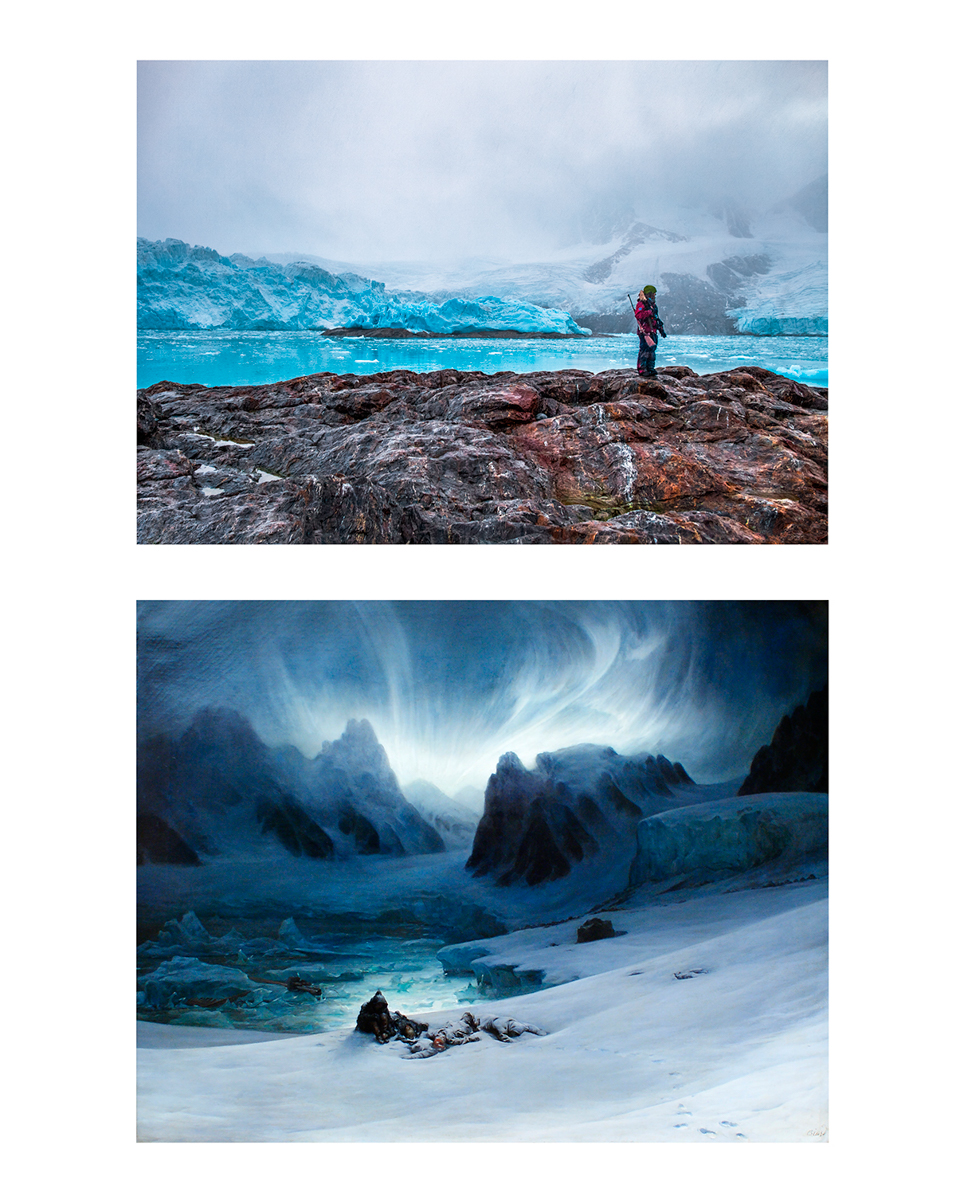

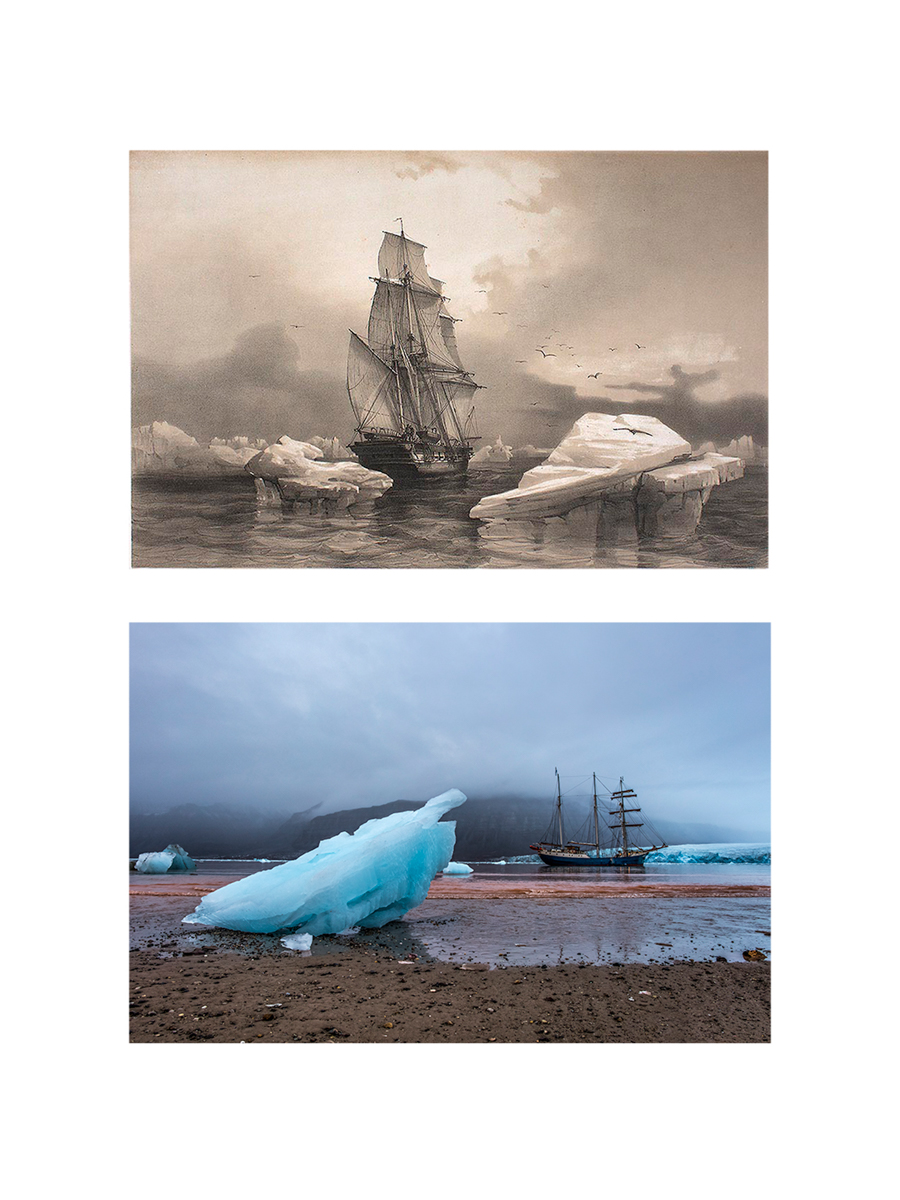

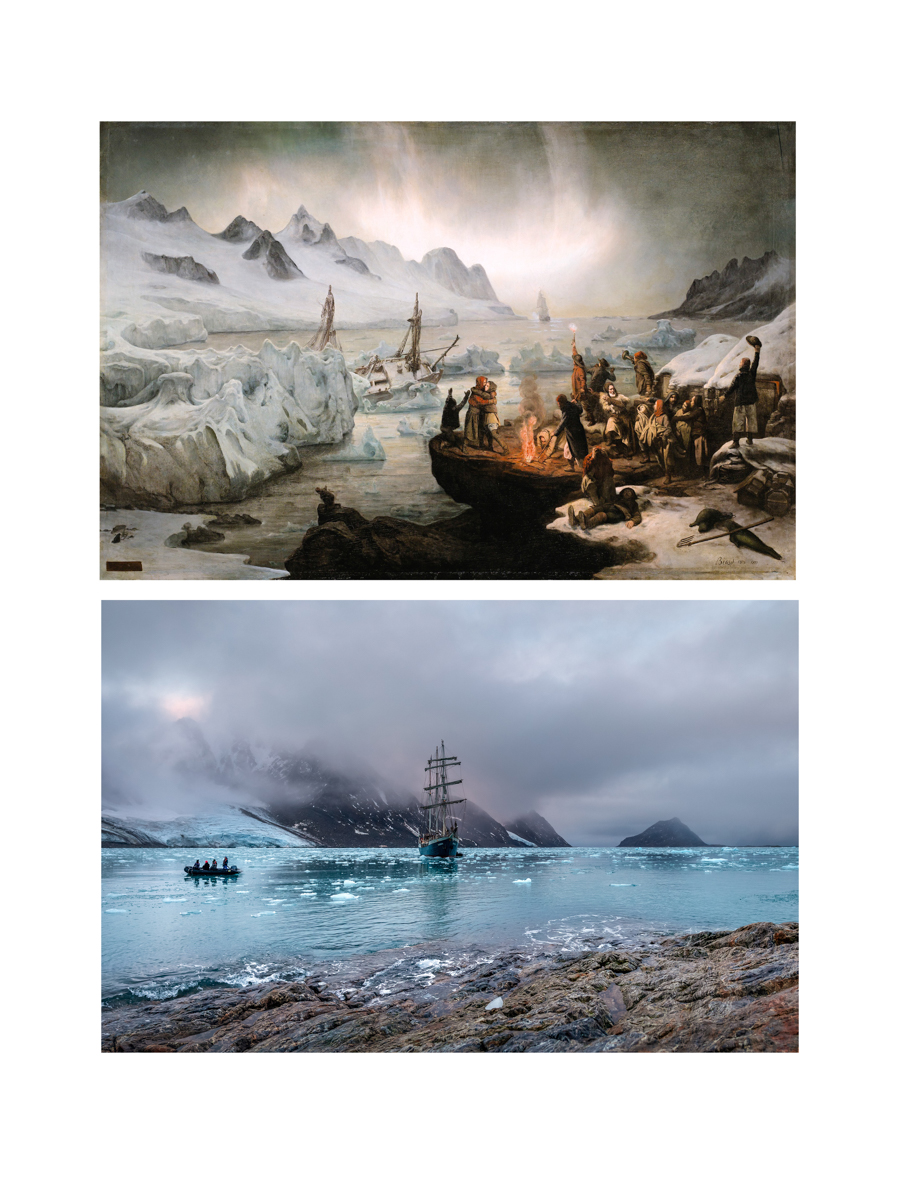

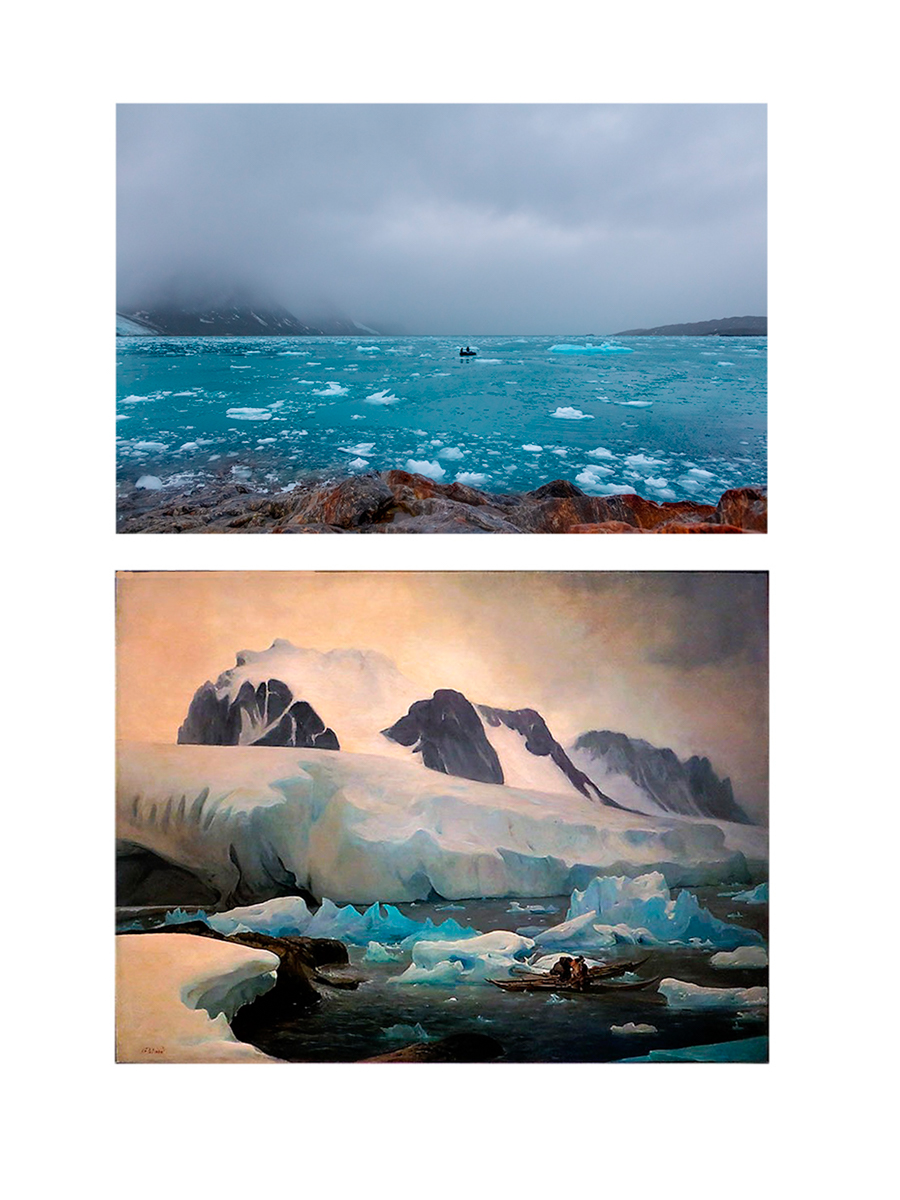

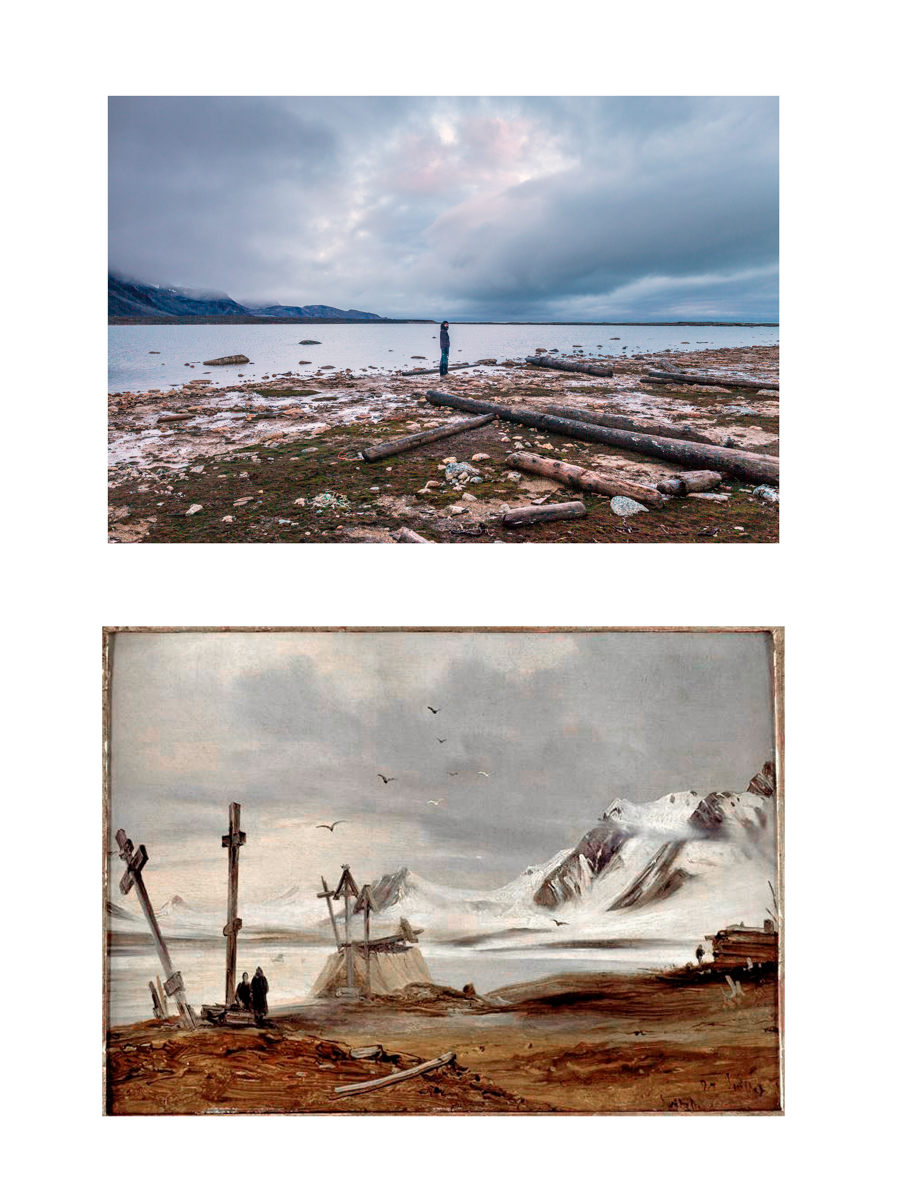

After that dense snow squall on the third we never saw snow again during our weeks at sea. As we made land each day we found ourselves wading through deep mud and when I photographed what remained of those early whaling stations along the northwest shores I found the wreckage of that first oil boom had been laid bare, the heavy rains and high seas devouring the graves of the hundreds of men who had been buried there, the foundations of building pooling was water. I carried in my pocket postcards of the many oil paintings that had been made over the centuries, and despite the dramatic climatic transformation there were eerie overlaps in the color and mood of the world we were passing through. I have paired several of the paintings with my photographs in the gallery below. Each is a reference to a real place—though not all of the painters had traveled there themselves but rather had been commissioned by the oil companies to create a celebration of this industrial triumph. In each painting you will find an act of imagination—the artist imagining a place he had never been but had heard and read so much about for the drama of the expansion of empire into the arctic was well known. The sailors paid for their own funerals before leaving home so dangerous was that short summer of work in the far north—the nearest trees after all were over 1500 kilometers to the south.